Current Issue

Contents

Introduction

Issue 18: The Space of Exchange

Exchange, from the simplest to the most complex of its forms, is fundamental to human life. The economic exchange of trade; the sharing of cultural traditions; the dialectics of disagreement, conflict, agreement, and resolution in political thinking and action; the negotiation of shared space or collaborative working; the individual’s place within a collective; knowledge shared and ideas debated; changing hearts and minds through conversation – all these are, consciously or not, part of our daily lives. And all of them take place in relation to actual as well as conceptual spaces: in the architecture of cities, streets, buildings, and rooms; around tables; over shared food and drink; on public transport; in parks, gardens, or allotments; in schools and universities; in galleries and museums; in factories, offices, workshops, and even artists’ studios.

Soanyway Issue 18 explores such spaces. We begin by featuring two very different collaborative art projects that both share the starting point of a table. We include one of these contributions, from Studio Kamillo in Rome, as our first artistic intervention into the space and exchange of Soanyway's publication space. We continue with our tradition of an exhibition feature with an account of the exhibition series Subject Platter at Corner7 in London. The wide-ranging contributions that follow include memories of school buildings; ruins in rural Portugal; an imaginative exploration of corners; a mother’s experience of travel and migration with her children, materialised through ceramics; acts of translation relating to borderline states; an encounter between a grieving daughter and her mother’s teenage lover; a graphic representation of the shadowy space of an urban passageway; a filmed encounter between a real and a painted figure; a sharing of their practice by three painters; a collaboration between a British writer and musician and a Dutch filmmaker; a conversation between two writers; the ethics and ecology of an urban community garden; and an insight into the inner workings of an artists’ collective.

An intervention from Studio Kamillo

Our studio is in the southeast of Rome, near the underground station Furio Camillo. We are a group of artists (Fabio Giorgi Alberti, Jacopo Rinaldi, Pierluigi Calignano, Lorenzo Pace), each with a different practice. We all have our own studio space, and there is a small kitchen, two bathrooms and a shared room. In this shared room there is a table. It is a big table, sugar paper blue, light blue – or sky blue, if you prefer.

The table is at the entrance of our studio (the studio is called Studio Kamillo). The floor in this entrance is not perfectly horizontal; it is slightly downhill. The surface of the table, however, is perfectly horizontal: so the side of the table that faces the entrance is low, and the opposite side is high.

The table is a table for work: on the surface there are the traces of things that have been worked upon there. We have often worked there on our own, in two, in three, in four, but I think never in five at the same time. We have had lunch on this table, and dinners. Someone got drunk on this table. But the table wanted more, so we had people reading poetry and playing music on it and around it.

The table still wants more, it wants to be a plinth for sculpture, a horizontal wall for hanging pictures or projecting video, it wants to be a stage for performance, or simply a place where a sewing machine could meet an umbrella. At the time of writing, it has so far hosted projects by Vieni Fortuna, by Angelica Gatto, by Antonio Perticara with text by Francesca Gallo, and there is more happening soon.

This table is a surface that wants to stimulate debate, ease encounters, create culture.

This table wants to escape our control, fly high and finally become.

An intervention by Fabio Giorgi Alberti for Studio Kamillo

The above intervention is a paper work for digital publication. It shows three table series, developing and playing with the definition, placement and role of the table.

Subject Platter at Corner7

by Derek Horton

Corner7 is a recently established Project Space in Camden, London. A valuable addition to the now-dwindling number of independent, artist-run gallery spaces in the UK capital, its programme includes performances, workshops and talks as well as exhibitions, with a focus on artistic collaboration and socially-engaged projects. Run by the artist Rose Davey, it is also home to her studio and a beautifully secluded courtyard garden, and it works in close collaboration with the neighbouring Rochester Square Ceramic Studio, including offering affordable accommodation for visiting artists working with clay.

Between November 2024 and February 2025, Corner7 was home to a series of exhibitions, events and dinners, under the collective title, Subject Platter.

Sign for the exhibition outside Corner7

At the heart, materially and conceptually, of this project was a bespoke table. Designed and constructed by the artist-maker Gary Woodley, the modular form of the table enabled it to be reconfigured in multiple ways, but always dominating and often all-but filling the entire gallery space. The gallery consists of two adjoining rooms on different levels, separated by three steps. The table maintained an even height as it travelled out across the steps, so that if seated at the table in the upper gallery you would be close to the floor, or in the lower gallery on stools of a conventional height. The table’s surfaces were painted in multiple muted colours by Rose Davey, and was accompanied with terracotta stools made by Francesca Anfossi.

Structurally, the table functioned throughout the project variously as a plinth, a stage, a base, a frame, a support, a barrier, a surface for communal dining. Central to all these uses, though, was its literal and metaphorical function as a space of exchange, between people, and between people and objects. Across all cultures the table is a meeting place, a gathering space, the site of sustenance and nourishment, a location for celebration and festivity, and a place of safety, security, and the comforts of home and family. Subject Platter emphasised these aspects in the particular context of our social and aesthetic experience of the pleasures of sharing artworks and exchanging ideas about them with artists.

The first artist in the Subject Platter sequence was Laura White. Her work has long been concerned with materiality and a process of experimentation in which she values the resistance of her chosen materials to her attempts to control them. Cracking, collapse, breakage, and failures open up new possible directions and solutions in a collaborative interaction between the artist and her materials. As the Ampersand Foundation Fellow at the British School at Rome, White spent 2022-23 in Italy, and seems to have been influenced by two contrasting historic movements in Italian sculpture: Arte povera of the 1960s and 70s, with its use of ‘poor’, humble, everyday or industrial materials, and the 17th century Baroque, with its theatricality, ornate flourishes, and elaborate, dynamic form. For Subject Platter, White made new works in dough, streaked with curlicues of marbled colour, in forms that twist and fold into and away from the surface of the table. Some, though not all, of the works were edible, and the exhibition included a dinner in which freshly made bread in various sculptural forms was shared by guests at the table, eaten and enjoyed with appropriate accompaniments from ceramic plates and vessels also made for the exhibition by the artist. Their tongue-like forms created a sensual and visceral experience to be seen and touched, whilst the bread sculptures were tasted and digested.

Installation view of Laura White's Table Baroque at Corner7

Laura White’s project was followed by The Best Leftovers by the sculptor Iain Hales, which combined several of Hales’ ongoing inspirations and recurring motifs: fragmented classical ruins, the conventions of museum display subverted from their usual function, and grid-like structures. He used Jesmonite, pigmented with pastel colours, to simulate ruined fluted columns and other architectural fragments, rendered in obviously handmade methods, set against manufactured galvanised grids held precariously in place by chocks and wedges some of which also function as candle sconces. Scattered apparently somewhat haphazardly across the surface of the modular table, the broken architectural fragments and half-burnt candles created a sculptural setting for a culminating event, Dinner Among the Ruins.

Installation view of Iain Hales The Best Leftovers at Corner7

The third iteration of Subject Platter featured Gabriele Beveridge. In a rather more minimal installation than the previous two, her sculptural vessels made of hand-blown glass were thoughtfully placed on the surfaces of the modular table, allowing each considerable space to ‘breathe’ – appropriate perhaps in the context of the carefully controlled human breath involved in their making. Lit by the daylight flooding through the gallery windows combined with its bright internal lights and white walls, the rich but subtle tints of the glass both complemented and were enriched by the interplay of reflection and refraction of the various pastel hues of the different modules of the table top. To amplify and further complicate this effect, each sculpture stood on a mirror. Although essentially abstract, the forms took on a distinctly figurative aspect in their resemblance to standing bodies, heads drooping downward in a reminder of both gravity and perhaps a certain air of weariness or resignation. In the spirit of the earlier events tying the sculptural form and materials to the conviviality of shared food and drink, melding the visual form of the artwork with a fundamental human function experienced haptically and sensually, at the private view wine was served in especially handmade glasses created by the artist at the National Glass Centre in Sunderland.

Installation view of Gabriele Beveridge's Bodies at Corner7

The fourth and final part of Subject Platter was a painting performance created by the artist Lisa Milroy. Milroy’s earlier painting practice has been expanded more recently into modes of installation and performance, introducing real time and space including the presence of people, and particularly the female body. In an interview some years ago, Milroy explained how she began to understand that “looking is an action, a form of work, residing in the body as much as the mind. […] In an installation painting that includes a performative component, a performer steps into the painting arena where she becomes absorbed by the art, part of the art, and then steps out into the world and takes the art with her, but also leaves it behind.” Altering some of the table components for the first time to form a low stage, for Subject Platter, Milroy presented Cloudy, a painting performance created for four performers, with original music by John Harding. Using elements of the weather as a metaphor for transformative change, and hope in the act of painting itself, Cloudy celebrated the idea that joy might be found in both art and nature’s meteorological forces. The performers were Minyoung Choi (cloud), Remi Ajani (rain), José Sarmiento (sun), and Antonia Caicedo Holguín (as the rainbow).

Installation view of Lisa Milton's Cloudy at Corner7

All featured photographs are by Crispian Blaize and Damian Griffiths, except for the Corner7 exterior shot, by Derek Horton.

Ashley Caruso - Tracing Impermanence: Ruins as Sites of Exchange in Rural Portugal

Casa de Camp

Ruins, often seen as static remnants of the past, hold immense potential as sites of exchange, where physical, cultural, and temporal boundaries intersect. This ongoing research into humble domestic ruins across rural Portugal examines the ruin as an ongoing exchange between what once was and what could be. It draws upon typology studies of the 1955-1961 Portuguese Folk Architecture Survey, government-driven cultural ruin initiatives, and the more experimental sound recordings of Michel Giacometti.

By employing experimental fieldwork methodologies, the study reimagines the role of the ruin as an active participant in a broader narrative of exchange, connecting human stories, environmental processes, and cultural memory.

Ruins are co-produced by time, nature, and human imagination-each layer adding depth to their meaning and significance. This references Jonathan Hill’s description on the ‘co-production of ruins’—a concept that suggests that ruins are not static or singular but are shaped by multiple hands over time, each contributing to their form and narrative.* The incremental modifications, whether intentional or not, add complexity to the structure, creating an ongoing expression of exchange, tracing multiple decisions and responses.

Satellite survey (a) mid section of land (b) ambiguous detail

Rammed earth wall (a) wall montage (b) detail

The project frames ruins as both stationary and transitional spaces of encounter: sites of human inhabitation, cultural loss, and environmental dialogue. In a broader European context, rural depopulation has led to the emergence of ‘ghost towns,’ where cultural heritage risks erasure yet retains the potential for creative reactivation. The practice-based research explores these dynamics through innovative site-specific recordings, uncovering exchanges across multiple dimensions:

-

Temporal Exchange: Documenting the interplay between past human activity and present decay, tracing the passage of time through chemically unfixed photographic processes and site-specific recordings.

-

Material Exchange: Capturing the interaction between built forms and natural processes, such as erosion and overgrowth, through drone imaging and infrared photography.

-

Cultural Exchange: Investigating shifts in identity, memory, and heritage as rural landscapes evolve, inspired by Michel Giacometti’s ethnographic sound recordings and contemporary documentary films by Catarina Alves Costa.

Various sites of exchange within this context reveal the nuanced dialogues present in ruins and their surroundings:

-

Rammed Earth Walls: Acting as boundaries that interact with time and elements, these walls retain traces of territorial boundaries and communal labour. At Casa de Campo, infrared photography and site-specific interventions document the transformation of these structures, illustrating their ongoing dialogue with the land.

-

Overgrown Pathways: Reclaimed by nature, these forgotten routes highlight the tension between human activity and natural reclamation. As experimental acts, walking, documenting and mapping interventions, inspired by Richard Long, retrace these paths to re-establish connections and reveal hidden narratives.

-

Collapsed Rooflines and Fragments: These architectural remnants frame views and filter light, creating suspended spaces that bridge inside and outside. Medium format film captures their ephemeral qualities, inviting reinterpretation.

-

Seasonal Riverbeds: Shifting between presence and absence, these natural features symbolise territorial negotiation and ecological change. Drone footage documents riverbeds at Casa de Campo, revealing their role in land ownership disputes and environmental narratives.

-

Abandoned Interiors: Weathered walls and decayed surfaces become spaces of atmospheric and acoustic exchange. Rooms that once facilitated human activity such as gathering, cooking, sleeping – are reimagined. Chemically unfixed photographic processes capture the layers of decay, echoing the impermanence of these interiors.

Through the lens of generation loss—the gradual erosion of information with each reproduction—the project highlights the fragility inherent in both ruins and their documentation. Inspired by Daisuke Yokota’s experimental image-making processes, the study embraces impermanence as a deliberate method to explore how time alters both subject and record.

Drone fieldwork recordings

By proposing experimental methodologies that challenge traditional modes of preservation, the research advocates for ruins to be seen as dynamic sites of exchange. These spaces embody the intersection of human and environmental forces, memory and decay, reality and imagination. The findings contribute to heritage preservation and cultural memory, urging readers to consider how innovative practices can transform ruins into meaningful encounters that bridge past, present, and future.

Preservation and conservation should extend beyond mere safeguarding, allowing ruins to evolve beyond static monuments in the landscape, and become sites where ideas intersect, fostering a dialogue between past and present. The additive value of each decision—those made by previous occupants and those shaping new interventions—creates a layered narrative of design exchange. Every response to the ruin acknowledges its history while contributing to its reimagination, transforming it into a living, evolving entity. By engaging with these spaces as sites of exchange, designers participate in an ongoing dialogue, where the past informs the present, and the present, in turn, projects new possibilities for the future.

Walking line (film stills)

NOTES

*Jonathan Hill, The Architecture of Ruins: Designs on the Past, Present and Future (London: Routledge, 2019), p. 295.

Clare Charnley and Joey Chin - Here but Where

…the lift conductor advised me not to waste a shilling to go up and see nothing, as it was foggy that day. I replied I was just wanting to see nothing… I walked around four sides of the tower and thought I was in heaven.

(Chiang Yee writing about visiting Westminster Cathedral in The Silent Traveller in London)

Keeping within a few hundred meters of where she lives, Clare Charnley photographs corners; that exact divide where two streets, paths or buildings join. Half of each photo is emptied out, leaving behind a white space with a single line. A place for Joey Chin, sixty-eight thousand miles away, to fill with other possibilities—a series of microfictions in response. These images evoke scenes that are implied, imagined, and invisible. They serve as starting points, visual sentences in the opening lines of a story, with what is hidden or obscured continuing to unfold through Joey’s words.

Included below is work from the collaborative image and text series Here but Where, made by Clare Charnley in Leeds, UK and Joey Chin in Singapore.

Giorgina Sexton - A Template for Memories

This series of photographs reflects upon the experience of moving between familiar and unfamiliar sites, as they exist in memory and the world outside, and the evocative idea of returning to a once-familiar site after a period of time has passed. The artist writes: "By chance, I found myself back one midweek afternoon, after the bells had rung loud and the shadows grew long. Each space now stood as a reminder of lessons learnt, memories made and time creeping along. The school, an empty template to observe, revisit and relive, the memories we've forgotten, invented, and remember."

Clare Carter - Guaguas

The word guagua (wa-wa) is known to be used exclusively in The Canary Islands, situated off the northwest coast of Africa, and Cuba in the Caribbean. It is a noun, meaning ‘bus’, and officially replaces the Latin-derived autobus typically used in mainland Spain and other Spanish-speaking countries. The Canary archipelago was the first land outside the geographical boundary of Europe to be colonised by Europeans in the 15th century, becoming a kindergarten for the Western imperialism that ensued.* Lanzarote was the first island to be colonised, wiping out the indigenous inhabitants – a Neolithic civilisation known as the Majos – in less than a century. Since this conquest, the islands have played a significant role in the exploration and colonisation of the New World and the Atlantic slave trade route, facilitating colonisation and capitalism across the world. There have been considerable migrations of Canarians to the Americas, usually due to drought, famine and volcanic eruptions. Migrations have been reciprocal from the Americas back across the Atlantic, and today The Canary Islands have a population with a substantial Latin American lineage. This is believed to be the reason guagua is used in The Canary Islands, however, its etymology is still disputed. Here are some possible explanations:

Wagon (n) from Dutch wagen; cognate with Old English wægn ‘farm wagon’, meaning vehicle in English; from Latin vehiculum, from veh(ere) ‘to carry, convey, ride’.

Awawa (v) ‘to move quickly’ in Ngu language, spoken by African slaves in Cuba.

Guagua (n) ‘baby' or ‘little child’ in Quechuan language, spoken in some parts of South America.

Guagua (adj) for ‘little, for nothing, for free’, spoken in Cuba (children are not charged for riding buses).

Wa & Wa Co. Inc (Washington & Walton Company Incorporated), an American transport company which manufactured some of the first passenger carriers in the 19th century in Cuba.

Guagua can also mean ‘a trivial matter’ in some parts of the Spanish-speaking world, and is a generic name for small insects that feast upon plants and citrus fruit.

I became a mother on the island of Lanzarote, and for the first time began to carry something inside my body whilst living within a desert landscape. This journey, of becoming a migrating vessel from my homeland of West Yorkshire to an island in the Atlantic, was also the beginning of a state of transformation; the slow unraveling of self in order to merge with another human body. This has brought me to thinking about the relationship between matter, landscape and caregiving. As I handle the clay like the flesh of the land, I am re-performing or mirroring the process of attending to a baby or young child, experiencing the intimacy of touch and the continuous, cyclical nature of caregiving. Like pulsating, widening circles, as my children grow older we are beginning to gradually move further away from each other, sometimes returning back to intimacy before orbiting out again into the world beyond the flesh. I see the clay as the space between our bodies, a reification of maternal agency, and how intimacy can sometimes be pushed to its limits and collapse in destructive ways, before more space is created to catch and hold the chaos of the other. Sometimes these spaces in the vessels can also speak about what isn’t there, what was lost, or what failed. If I consider all the possible meanings of the word guagua, I find a deeper layer hidden beneath my maternal relationship with the landscape of Lanzarote, one that embodies a darker, historical foundation of Western imperialism and colonisation, of displacement and migration that is left in the wake of capitalism and the unfolding Anthropocene. Guagua is many things… it is the vehicle taking its traveller to a different landscape… it is the wa-wa-wah feeling of moving my body across a landscape… it is the wind wrapping and running through my hair... it is the waves carrying bodies across the Atlantic... it is coiling clay and making marks across the space of a page... it is my body as a house and vessel, carefully carrying a little baby in my arms… it is the unravelling of self for another body… and it is the corporate branding of a mode of transportation navigating a world built upon the exploitation of bodies and land as resources.

This text, written in response to a series of ceramic vessels called Guaguas created in 2024, is featured in an artist book (pictured above) containing drawings and photographs taken during travels to the island of Lanzarote with my children between 2019 and 2024.

NOTES

* Sven Lindquist, Exterminate All the Brutes (London: Granta Books, 1996), p.111.

Mark Wingrave - Borderline States

On the morning after my first night in Narva. I stepped out onto worn roads, the late summer light on tall trees and crumbling facades. I passed the closed pedestrian river border crossing, the cameras and razor wire and crossed Joala street. Then, around a corner, Kreenholm. Once the largest textile site in the Russian Empire, it spans the western bank and a couple of islands in the Narva River. Established in the 19th century it continued production throughout Soviet and post-perestroika times until its demise in 2010.

Kreenholm

Narva is in the eastern most point of Estonia, and sits at the limit of European Union influence and NATO power. Narva and Ivangorod castles face each other across the river which marks the Estonian – Russian border. In Autumn of 2024, I spent a couple of months in the city as an artist in residence at NART. An installation in the abandoned industrial zone of Kreenholm would become one element of the three-part project that I completed while in Narva – and exhibition and poetry reading – based on collaboration between myself, a visual artist, and Larissa Joonas an Estonian poet writing in Russian.

I came across a group of poems by Larissa in 2022 and translated them. This coincided with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Larissa wrote:

Unaware the war had struck the core of me

I see now it's turned up inside me

so burned up inside there's little left of me

still I am like an incendiary shield

an ever present secure border

sealing each loophole by my body

there's no way a flash of pure hate

will ever break out of me and blaze

the now dumbfounded fearful world.

At this time, I was also reading a lot of social media posts of Russian and Ukrainian friends, and translators and journalists about killings, destruction, fears, disruption and resolve. From my own vantage point in Melbourne, art residences in Russian cities that had been offered to me were cancelled. A Ukrainian friend was killed in Bakhmut.

Larissa's moving poems about war and trauma grapple with this emerging sense of division and loss. I translated a number of her poems into English and Larissa and I started what has become an extended conversation.

Over this time I started translating Larissa's poetry from Russian into English and communicating with her on a regular basis. The project for the residency grew out of this exchange. Our messages – initially on matters regarding translations: specifically about words, phrases – extended to shared interests in art, film and literature. We first met at Jõhve coach station. After exchanging gifts we continued conversations begun online while walking together.

Exchange of gifts: Larissa Joonas, The Flight Radar Wastelands

It was the setting for a Russian merchant's palace that later became the summer residence of the Estonian president before it was destroyed by the Soviets during WWII.

I walked on dead words

at times raising them reviving them

warming them in my hands nurturing them in my garden

like in a kindergarten like in paradise so cocooned

amongst carved leaves and ripe round fruit

in the flickering mellow light

where no one has to leave this life.

The installation at Kreenholm consisted of one of Larissa’s poems strung between columns in one of the empty spinning machine halls. I exhibited folded drawings with hand-drawn and translated phrases from different poems.

Finally, there was a poetry reading with Larissa (in Russian), Aare Pilv (Estonian translations) and myself (English translations). When Larissa read her poems both Aare and I looked at each other as if a light had lit up our understanding – he said to me "this is how I need to translate her". Her voice and her poems are all about breath, a life force. I use translation to develop the relationship between writing and painting, and thereby explore what can be expressed verbally and visually.

On my return to Melbourne I made a video that combines images of the Kreenholm installation with a recording of Larissa reading with English subtitles.

At a time when the world is increasingly divided, art and translation are vital in understanding and imagining worlds beyond our own.

Joanna Craddock - In Dialogue

I met the man who, in the late 1950's, had been my mother's art school lover, and who, long before I was born, she was prohibited from seeing again. We met at a Belfast cafe. I was a wreck after the family had scattered mum's ashes into the sea, and now transgressing into foreclosed territory, a business not my own, carrying on a carry on. And yet I did so. What struck me most about the meeting was the everydayness of things around me as I approached the table where he was sitting, then standing to greet me. The way in which the chairs were positioned as I walked toward him; placed to welcome, open, a gesture which has continued to impress itself upon me. It begged the question 'Who will you sit with; who is welcome at the table?'

I have often tried to imagine my mother's experience as a child, the austere environment, the house church and meeting room and what that might have been like. The order of the space, the sounds, the weight of the furniture, the light, the smell of the pages at the bible addresses teaching the wholly inspired and infallible truth; about who's in and who's out. I have wondered about the psychological spaces she would have had to inhabit as a young woman, and the physical spaces she would have to find to be able to embrace the one whom she chose; secretly, guiltily, pushed beyond the pale. And those, who, from shame, have to choose to travel through life to visibly agreeably fit within convention.

… grafik 2.1 - … [and] the transient trace, the mark made [lost: found]

… not in the thing itself but in the patterns of shadows, the light and the darkness, that one thing against another creates.

Junichiro Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows (London: Vintage 2001), p. 46.

Applying a CMYK palette towards the creation of a monochromatic aesthetic, the works allude to the implicit presence of fragmented narratives present within the urban passageway. These works explore an interaction between sensations of permanence and transience within mark-making, between light and darkness, and traces left of presence, emotion and exchange.

![… [and] loves me, loves me not [carved: etched]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/80d7cb_863ec1bdccf1442dad01b83a299d1410~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_980,h_980,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/80d7cb_863ec1bdccf1442dad01b83a299d1410~mv2.jpg)

2023, From an Edition of: 12

![… [and] here, lying naked upon your floor [torn: uncertain]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/80d7cb_4efed16d4f8f4eaaab07377bbd91ac56~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_980,h_980,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/80d7cb_4efed16d4f8f4eaaab07377bbd91ac56~mv2.jpg)

2024, From an Edition of: 10

![… [and] more than darkness lies between us [eyes: mouth] [tentative: adjoined]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/80d7cb_a59c30a398874dd28ecd8101c0aea5c6~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_980,h_980,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/80d7cb_a59c30a398874dd28ecd8101c0aea5c6~mv2.jpg)

2024, From an Edition of: 12

![… [and] loves me, loves me not [carved: etched]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/80d7cb_863ec1bdccf1442dad01b83a299d1410~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_980,h_980,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/80d7cb_863ec1bdccf1442dad01b83a299d1410~mv2.jpg)

2023, From an Edition of: 12

Medium: Silkscreen Print: Image: 40 x 40cm. Paper: 56 x 58cm. Paper: Somerset Satin White Tub 600gsm.

Nadine Feinson - Embodiment: Big Daddy & Michael

The film Embodiment: Big Daddy & Michael (8 minutes) is one of 5 short films by the artist that explore the possibility of exchange, attunement and communication between a human participant and freestanding paper figure / artwork. Sound is a key narrative component. The participant was asked to approach the paper figure (an ‘embodiment’) as if it were ‘real’, but a different order of being. Emerging from this was a process of drawing in and drawing out through touch, empathy and the activation of memory; moments of frustration and disconnect alongside tenderness and understanding. These exchanges were unscripted.

Simone Bennett and Boff Whalley - Collaboration, Fire and Invisible Owls

From the series Anchors. Photographs printed on Hahnemühle fine art pearl paper 2020. (Simone Bennett)

18 October 2023: Meeting as strangers. Coming together with a similar interest: fire. Simone meets Boff at the Tetley in Leeds while she is working on a project about fire in Leeds. From this moment on, working together becomes a path towards a future project.

A collaboration unfolds on its own timeline; what’s important is that the connection is there. In a collaboration, sometimes the connective wish comes first, and the spark of the idea follows – and sometimes, it’s the other way around.

Simone: The idea starts traveling a long or short distance, finding just the right people and conditions to start a new work, to catch fire, to take hold.

With collaborators there is a code hidden in conversation, and this code alerts you to a connection. You say this, I say that, and there is a jumping-off point somewhere in that gap between this and that. A mind-map crosses the space, and you realise that with the person you collaborate you are allowed to be brave about stupid, weird, mad ideas, without being judged for it.

Boff: And of course, the ideas can be transformed, can often become more interesting than you could ever imagine. And looking at all the big examples of creative collaboration, there is a pattern, and the pattern tells us that even when one artist gets the credit, the ideas flow from two, three, four, a hundred, thousands of people. Ideas built from the crazy, constantly moving connections on the hive-mind map. Look, the space between us is filled with ideas!

Simone: The connections and collaborations are historical, too. Across the arts, you continually build upon the works of those who worked before you. When my father died, he left me and my brother 1000s of works – finished works, half works, sketches – everything was piled up in his studio, and for a whole year we went through his drawings and sketches to sort them. While we were doing this, I felt like I inherited his eyes. And just by building upon the energy he had started, new ideas and thoughts entered my head. Collaborating with ancestors and artists who have passed feels like folding back time, erasing the distance that is standing between you and them.

The big hand in the photograph is of my father.

25 March 2024: Simone emails Boff. The spark arrives through the work of the artist Stephen Cripps (1952-1982). Stephen Cripps brings together so many of our shared interests. Stephen Cripps was an incredible performance artist who worked with pyrotechnics and sound and was also a firefighter. What remains of his work – sketches, films, sounds and photos – is archived and lives in 33 boxes at the Henry Moore Research Centre in Leeds and in Acme in London.

Simone: Sometimes an idea works like a magnet, collecting similar ideas from all the hidden spaces around us. If you read a book about owls then you will suddenly see images of owls all around you, owls that you never noticed before!

Boff: Brian Eno talks about how human brains are not (as we always imagine) getting bigger, but are shrinking. And the reason for this is that we have learned over many thousands of years how to specialize and share, we are in a constant collaboration with so many people (engineers, scientists, inventors, etc) every time we catch a bus or buy a loaf of bread. And this is true of making a painting or writing a song.

As humans we have learned to filter out (and even reject) the things we don’t need. Last year I saw the stunning Caravaggio paintings in Napoli, hanging in huge old churches. To see them is to realise how as an artist he was both learning from the past masters, and rejecting them at the same time. Taking from the old, bringing in the new.

23 October 2024: Boff and Simone dive into the Henry Moore Research Archive, and all the plans, works, sounds and films of Stephen Cripps become starting points on sharing new ideas. The beauty of collaboration is that it naturally attracts even more collaborators into the project.

Simone: When we work together, we have to be truly open to those ideas. Open your arms (and eyes, and ears) and allow ideas in, quickly, before they leave the room in search of other makers who may be more welcoming. For this is a call to adventure – one that shouldn’t be over-questioned or analysed in its starting form, when it’s still tender and delicate, when it’s a bit dumb and needs to grow stronger while you work with it, mould it, push it gently, shape it into form.

23 October 2024: Fuelled by what they find in the archive, Simone and Boff start working with Commoners Choir, practicing with the choir using sounds instead of singing. They stand in front of the choir of 60 voices and encourage them to make noises like fireworks, with explosions and screams. And like a fire, it catches on, the noises organize themselves and begin to work together. It’s a start for a new film sound work.

Boff: Ideas, like adventures, can fail. Failure is such an important part of creativity. Being able to fail in public – in front of the people you are collaborating with – is essential. We have to be taught how to light a fire (I light one each winter morning in my house) and we have to make a hundred mistakes to begin to know how to make the perfect fire. Malcolm McLaren said that the best lesson he was ever taught was how to embrace failure. Don’t be afraid of failure.

Simone: Some collaborations fail wonderfully. Embers fading out long before they have a chance to ignite a fire… but instead, something else happens, something completely different is learned. Like the anecdote about two neighbours in Devon, England, who unknowingly spent an entire year hooting at each other, thinking they were communicating with owls.

Boff: That’s it, exactly. Hooting with the invisible owls.

shapes&colours&things: Emma Bolland, Stu Burke, Gary Simmonds - Salon #1 Dialogues

shapes&colours&things is a collective research group consisting of Emma Bolland, Stu Burke and Gary Simmonds, whose interests intersect somewhere within contemporary painting and geometry. Through a series of studio visits, the artists cross-pollinated their painterly thinking through dialogue: taking photographs as conversation, they documented their sharing of space and ideas. This is a collaboration of images from all their studios and depicts the meeting place of the three artists as painters. The use of location lines, used in screenwriting, translate the images, pages, into a conceptual three-person play.

Rachel Cattle and Eileen Daly - Side by Side

Over the last year Rachel Cattle and Eileen Daly have been speaking in person and via email about the non-institutional community of artists, writers and editors that co-exist around their writing practices.

ED: With the Leonard Bast poem I’m working on, I’d been thinking about Bast being angry and realised that I was angry too. What’s that about? Anger is familiar to me – not shouty anger but something more fundamental. Anyway I let it sit around for a bit and then wrote some more. I come to the Bast character in Howards End with empathy, joy, expectation and yet he is dismissed. To me, his night-walking is thrilling, I’m envious.

RC: I was really struck by … 'I let it sit around for a bit'. As if anger was a person, an entity. And I totally get that you're writing through Bast's anger (about class? Is there other stuff too … feeling dismissed?).

There’s a kind of chaos within my own writing. I’m currently taking bits I've written as emails to myself, deliberately putting them somewhere random in the manuscript – bypassing my conscious mind to find strange meetings or overlaps I can then work with. Which is exactly how collage works … maybe I’m seeing my writing as an artwork I'm making.

I’ve been writing about an art gallery. It has a space in the roof that I've been going into. First I wondered if the gallery director kept stuff up there, hidden things, her money, stolen artworks, then it was old newspapers, bits of junk and then I thought maybe I was the space. Then the space just seemed strange, and then it also became the space of my dad … this unknowable thing I longed for.

ED: That hidden space in the gallery made me think of the Studio space at the ICA. When I was last there the door to the Studio was open and I could see the breeze block walls and wires hanging down and the scruffiness of the corridor leading to the space. In the writing when you say you’re looking around at all the things that are in there (or might be in there) and it becoming the space of your dad, I totally get that. The Leonard Bast piece encompasses anger, the loss of my mum, watery habitats … these things may feel disparate but they also have a place alongside each other.

RC: … when I did the PhD at Kingston School of Art we did a lot of presentations in that ICA Studio and it struck me how much it felt like some strange form of group therapy, because you are quite exposed in that situation. You’re presenting work to your peers that’s really unformed, plus you're trying to get both inside your own work/methods and simultaneously standing outside them … and do all this publicly. It’s a head fuck on many levels, but also immersive and interesting – it changed me.

ED: The Leonard Bast poem is now two poems. Still feeling angry though.

RC: I sat on the sofa last night and read through my writing. I've decided to dress up as the gallery director – to see if I can 'play her' – which is making me feel a bit sick (in the writing) wearing her itchy skirt; I've put it over my head and turned it into a weird mask.

ED: When I read the above, I thought you said you were ACTUALLY dressing up (AND GOING OUT) as the gallery director. Is that what this means? Sounds great if it is.

RC: … and thanks for the walk around the lake at the Barbican. The lake in my writing is becoming important. When I talk to anyone about it I keep trying to grasp at 'what it’s about' … I start talking about the gallery, or the acting as the gallery director, or the lake … but I'm not sure it’s about these things at all. Anyway, what the writing 'is' is what keeps me interested … stuff appears and if you push at it a bit more stuff crops up … like magic, like it isn't even yours.

ED: Last night I picked up The Young Man by Annie Ernaux. It’s the thinnest book and something I read struck a chord with our conversation: ‘Work for him meant nothing more than a constraint with which he did not wish to comply, if other ways of life were possible. Having a profession had been, and remained, the condition of my freedom, given the relative uncertainty of my books meeting with success …’

I read into this Ernaux saying how the working life can seem different from the writing life but for her generation the right to work outside of the home had been a liberation, and that writing and ‘having a profession’ are part of the same thing. More and more I think of all of what I do as being part of writing, rather than separating it out.

It’s funny that you mention the word ‘lake’ as that word is in the Bast poem. I attach it here. I agree; the ‘lake’ in my poem is also important and I’m also not sure why.

RC: … I love this! The Bast poem … I'm attaching a piece of my own writing in response.

ED: It’s really appealing how in your piece, the paragraphs have no end punctuation and that they all start with lower case letters. It feels like they are carrying on somewhere else off page (off screen) – they still make sense within the whole, so it’s not that the architecture of this makes it feel disconnected.

RC: With the Bast poem I wanted to reply with my own writing, something to do with the ideas of conversation within it … and talking about the way my writing seems to go off screen (page) … I feel the Bast book (Howards End) is going on all the way through the poem – and how you move between the thing of Bast talking about how he feels and talking about 'us' three and how that felt, time slipping, real time, remembered time, book time … waking time.

…also, the other day, when I said I intentionally didn’t go to the Philip Guston show at Tate and you said that was quite 'wilful', I thought I hadn't heard that word in a while … and I liked it. I was probably always a 'wilful child' and what does that mean? I like its sound …

ED: Yes, the wilful child – there were a lot of them around growing up. Are they still out there (still wilful)?

But Not Only

I have your voice not in my ear but in my head. I can’t always hear the words – there are none – but I know I am listening to a conversation we had some time ago. We were both facing East at the time. Are words talismans? Over and over we spoke, pause, speak again, mainly me. Carrying our words back and forth. I’m listening out for echo, not that I knew it at the time.

Some nights ago I walked outside in the dark. The streets were fairly busy, it was not late, and I saw thru (them) the trees, the path, the moon. I was minded of Leonard Bast walking to the woods in the suburbs: was he looking for agency or for something to happen? Some time later he chose to speak of his desire to walk all night, in the dark. At that moment he had probably not spoken of this to anyone else and was exercising his thoughts first-hand. On the day of the people and the moon, inside the room, there were slight movements, us three. Did the walk have an effect?

In between the silence and responses, there was a walk to a manmade lake. Was the lake manmade? The buildings around the lake were positioned in a kind of stepped design, appearing bigger to the eye overall than they were when you walked in, between and around them. At the high point, where the upper buildings met the wood, were some steps cut into the earth with logs placed horizontally to form stepping points. It gave the suggestion that there would be something at the top – a viewpoint? However, it appeared only to be a practicality: a small building to organise something to do with water (flow); the water was gurgling, babbling continuously. Was it a filtering system to capture the water from the mountain spring? How do unspoken words sound? Their length, their shape, their tone?

Eileen Daly

TU LIP

I’m standing in the middle of the gallery roof space, the Gallery Director’s itchy dress is pulled right over my head and I’ve fashioned it into some kind of bat-like animal mask – it’s huge, extends outwards almost touching the walls. I’m going to tell you about a job I had, I say, muffled.

Downstairs in the gallery kitchen, the Gallery Director stands alert in the centre of the room, hands in the air, sleeves slightly rolled, unable to move, staring at the worksurfaces. Lined up in front of her is a row of tins containing varieties of expensive teas, and next to these, boxes in varying states of repair containing more bog-standard tea – PG Tips and some herbal teabags, and next to these a coffee filter machine which has coffee grounds all up the sides, and a brown ring around its base, smudged onto the worksurface. She grimaces. The gallery has a policy of everyone taking turns to make lunch to encourage camaraderie and a non-hierarchical attitude amongst the staff. The Gallery Director is usually able to get out of this situation, has done for years in fact, but today, she is somehow here in this room, without an excuse.

At home Dad starts going to evening classes, makes metal objects, delicate beautiful things, a round bowl with repeated circles he has cut out of its lid, a copper cylinder, he meets his girlfriend there at night and comes back home and shows us the objects.

I clear my throat beneath the mask and start again…

Rachel Cattle

Sean Roy Parker - Post-Rational Relations in the Community Garden

On becoming a frequent visitor to a green space, as a bee or butterfly or bird might be, I begin to notice some of the natural rhythms occurring, and can glean fragments of useful information. If I pick the right time and direction to look in, the speedy growth of a patch of nettles, the sudden appearance of tadpoles in a pond, and the sharp temperature drop at dusk will all happily show themselves.

Organic lifecycles don’t just move in one direction like our industrial timeline, instead they are non-linear – ellipses, waves, spirals – and multilayered. Periods of growth, change and rest are gently shaped by the seasons, and help paint a detailed picture of the delicately balanced ecosystems that rely on them. Once I was able to observe and embrace these subtle differences from our own existence, it made me think about my presence in their space.

Many gardeners, poets, writers and artists argue that capitalism has taught us that humans are the dominant species on Earth, so it might seem logical we control wildness to prove and reinforce the hierarchy. However, by dropping the human-centred narrative, we see all plants as our equals: independent thinkers that strive to communicate with each other; sentient beings that require care, respect and understanding; soft bodies that need water, warmth, heat and oxygen. If we stare at the dandelions, listen to the oaks and talk with the rosemary, they will tell us everything we need to support their flourishing, and as Robin Wall Kimmerer tells us, “All Flourishing is Mutual”.

I have an idea for us to try together. It might help realise our placement within a deep entanglement of ecology, a complex web of life. It might help us see our more damaging habits more clearly. It might help us find a new approach to bonding with vegetation. Yesterday was the best time to make a change. The second best is today.

What if we agreed that we are not taking

the flowers

the fruits

the nuts

the cones

the seeds

the leaves

the stems

the bark

the roots?

What if we agreed that plants are gifting them to us?

I wouldn’t steal something from a human friend, so why from a more-than-human one? It’s a privilege to receive food from plants. That they share parts of themselves that will not kill us is generous; that some of these parts hold properties that make them nutritious, medicinal or practical to us is miraculous.

We can reciprocate the care plants show us in a number of small ways, some symbolic and others more literal. I like to talk to wild herbs when I am collecting, asking how their day is and paying them compliments. One friend asks them whether they would mind sharing their bounty and says they always give a clear answer back. Another sprinkles a homemade tea blend on the soil next to the giving plants. Undoubtedly the most important gift we can return is intentional care: to only take what we need and do our best to protect and enrich the soil.

Our relationship to the natural world can be very alienating when there are so many barriers to accessing even our most basic needs: food, water, shelter, warmth, human touch. We are consistently warned of these running out and encouraged to engage in competitive behaviours in order to ensure our survival. I would argue this creates fear around scarcity, and if we are able to look beyond this economic tactic, we can tap into the abundance of resources that we already have around us and within ourselves.

Money is no measure of someone’s worth. In our consumer society, where so much emphasis is placed on financial and material wealth, we must leave behind some popular ideas of value which don’t take into account the luck of being born into fortune or safety, and instead experiment with alternatives that bring us closer together and forge new appreciation of our individual and others’ collective qualities.

Since we have established that all food, medicine and textiles from plants are an incredible gift, I think we can push a little further and consider how we can share our human time / energy / tools / ideas / knowledge / skill / love without requiring something in return. Exchanging any amount of these for money is to attach a rational number to something that is abstract or intangible. It’s like trying to buy a feeling or particle of air.

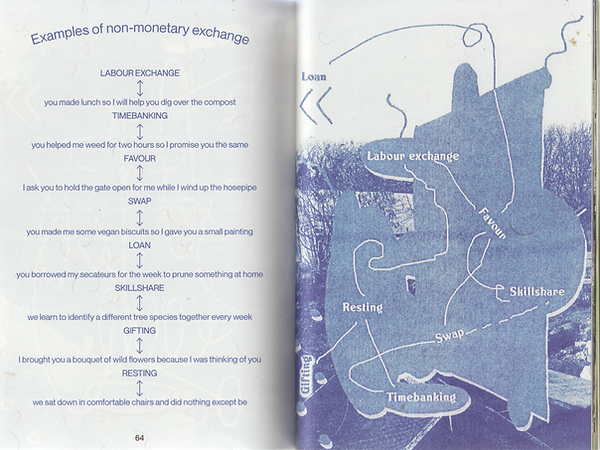

By removing this rigid expectation of like-for-like, we can build new structures of value like trust, friendship and solidarity. These structures can be strong and robust, yet soft and flexible. They can be tried and tested, or never fully formed. They can bring out the best in ourselves, and uncover hidden talents. In our greenspaces, where money has no value, and people mean everything, let’s look at some of the ways we’re already building connections.

Images by Sean Roy Parker, interpreted for print by Holly Eliza Temple.

TOTALLER - A Meeting of the Friends of TOTALLER

'A Meeting of the Friends of TOTALLER' was an event held in the project space of The Northern Charter studios, Pilgrim Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, in November 2019. TOTALLER is an artist collective with between two and eight core members that works with a broader network of artists on various projects. The Northern Charter was a studio block situated on the fifth floor of Commercial Union House, a modernist building in central Newcastle. The following text and images describe and document the event.

Loosely inspired by the structure of a Quaker Friends’ Meeting, the event is a gathering of members of TOTALLER and friends of the collective warmly invited to take part. Not everyone present has met before, so there are friendly introductions and greetings before the more structured parts of the evening begin.

Various office chairs are arranged in a circle in the large open room. There is a vinyl banner on the floor in the circle’s centre. One by one everyone sits, gets used to their chair and looks at the banner. It shows a reproduction of a drawing of soldiers in Roman Britain bunched into a testudo formation, interlocking shields raised above their heads. All we can see of them is their muscular legs, their shorts and sandals. They are being pelted with rocks by enemies on a fortified wall. The banner itself has been pelted with tomatoes at a past event and has a dull coating of dry juice.

We are invited by a member of TOTALLER to sit quietly with our thoughts, to think about the image on the banner if we wish to, or not. If we feel the desire to speak, we are free to do so. The chatter stops.

The sound of a shuffled foot or the creak of a chair leg becomes amplified in the hush. Someone clears their throat. There is a quietness to the room despite the noises entering through the open windows. Shouts and electronic sounds echo up from the streets. There is a rumble of bus engines from down below. The air of the evening is saturated with a concentration of sounds.

Someone in the circle begins to speak, and focuses shift to their words. They talk about their work in a bureaucratised and hostile university environment, and of their frustration with this. The gathering returns to silence.

Someone shares a memory of cutting firewood for a relative on a winter night, and eating a very cold Mars Bar. Quiet ensues again.

Someone describes with affection the arms of their lover. We listen to the sounds of the room or our thoughts again, and we are invited to have a break from the chairs, to have a stretch and relax.

Some folding tables are laid out with food, and we eat snacks together — cheap crisps, chocolate mini-rolls, biscuits, and drink glasses of juice and water.

A rectangle of plywood is leant against the back of each chair. We use these to re-enact the shield wall from the drawing on the banner, which is scanned from a dog-eared postcard bought at Segedunum Roman fort, in Wallsend. There is concentration, clattering, and laughter as our testudo shuffles ungraciously across the studio, inch-by-inch, knocking into the office chairs. In Latin, testudo means tortoise or turtle, which to TOTALLER brings associations with the 1990s cartoon, the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

Unprompted, someone goes for markers and crayons and we draw on our shields.

The building we are in is a stark pebble-covered hulk of a building straddling the street; the bus stops and pavement are directly below. The structural columns that hold it aloft rise from a traffic island of decoratively laid granite setts, planted right in the middle of Pilgrim Street. Several years later the building will be demolished. The Northern Charter and various other arts organisations based at Commercial Union House will be forced to find somewhere else to exist, or will come to an end.

The friends go home and we, the members of TOTALLER, tidy up the food, and chat and laugh, high on the night. We roll up the banner and fold down the tables. We look at the drawings on the shields as we stack them neatly aside. Later, the shields will be swallowed up in the rubble of demolition.