by Karen Whiteson

The shadowy quality of the work’s documentary vestiges will act as a memento to the missing body of the book. Printed as a statement of intent on the back cover of the sculptor Katrina Palmer’s book ‘End Matter’, this extract underlines that which the title suggests, i.e. this is a book constituted entirely of its own supplementary material. Whether or not the main corpus ever existed in the first place is one of several riddles which serve to baffle and fascinate the collective figure of the Loss Adjusters. A metaphysical version of the insurance agent who assesses the amount of compensation to be paid following a claim, the Adjusters’ main remit is to account for the loss of land mass from the isle of Portland, and attempt to counterbalance it with presence. The title of one their (missing)dossiers is ‘Compensating for the Depletion of Real Things with Fictionality’. Here, the idea of fiction as a hallucination arising out of emptiness is embedded the landscape. Portland stone supplies the building material for the bulk of London’s civic edifices; a million square feet was quarried for Saint Paul’s cathedral alone. The hollowing out of the bedrock renders it a site acutely vulnerable to fabulists. And, one might add, allegorists; at least going by Walter Benjamin’s aphorism that Allegory is in the realm of thought as ruins are in the realm of things.

According to Benjamin, the gaze, charged with a sense of transience, falls upon its object, hollowing it out of any meaning except that which it acquires through interpretation. For Benjamin the melancholic gaze is the essence of the allegorical mindset. Hence The Loss Adjusters are at all times woeful: an inherent disposition confirmed by their proximity to Portland stone. The allegorical emblem par excellence is the ruin; through its re-absorption into the landscape the built environment becomes memento mori. In allegory, Benjamin states, the observer is confronted with the facies hippocratica of history as a petrified, primordial landscape. Only here, the ruin is not the crumbled edifice but a terrain hollowed out by the quarrymen and convicts; those who cut the stones which go to build the capital, leaving behind a negative space, an ancient landscape palpably charged with loss. The landscape as its own ruin and memorial in one: the ruin as readymade. At least, so it becomes as witnessed by the Loss Adjusters: What is not here is commemorated at the site of its disappearance. The entire island is a Portland stone memorial, carved out and immense, shaped by convicts and quarrymen, sliced and dissected by the machine, and perceived as an ongoing sculptural production created by loss.

In ‘End Matter’ missing bodies comprised of both text and flesh – dislodged stones and the sound of implements hitting rock – are some of recurring motifs embedded just under the surface of the narrative, where the threads of the story merge and loop to form a subterranean labyrinth. Dense with ideas, the book also delivers a rattling good yarn.

These tales are presented as deleted fragments, retrieved and pored over by the Adjusters; the work of a writer in residence who has herself gone awol. These fragments concern the quarryman’s two “deviant” daughters, a Carniter and his dealings with a Rogue Loss Adjuster and Ash, a young convict. The first tale features sisters Celestine and Hazeline, themselves supplementary creatures who having outlived their father’s traditional occupation of quarrying, have no place in the social structure. But here we are. As Celestine says. Displaced by time yet stubbornly present in space they’re like the mound of earth which appears when Ash buries the Rogue’s corpse. Their excessive love of the landscape binds them to the island. One day Hazeline recounts to her sister a peculiar encounter with the Adjusters. The encounter begins with them questioning her in the interests of their bureaucratic research, but this soon turns into a group sex scene described in terms of a machinic assembly of moving parts, a merging of flesh with stone. As Celestine wryly comments: There’s a long history of banging and cutting on this island. I hope they thanked you. The link between the sex scene and the exertion of labour required to extract the stone is continually evoked throughout the book, underlining its theme of sacrifice and expenditure.

This orgiastic scene triggers the event of a runaway horse whose mad dash across the island culminates in the dislodging of a huge boulder which crushes Hazeline’s hut, along with a human inhabitant of the island, (the identity of the crushed remains supplies one of several story hooks). The elemental force of the runaway horse is conjured in a singular sonic image: Its heavy hooves powered down and into the ground. Those hoofbeats sustain their echo in the recurring descriptions of men working stone: Co-ordinated sound resonated throughout the arena; the repeated impact of iron against rock. The power required for a human body to force a pickaxe through stone required this rhythm.

This book is part of a tripartite work commissioned by Artangel and these interlocking tales have been repurposed for an audio piece which accompanies a site specific walk, as well for a broadcast on BBC Radio 4. This juxtapositioning of the written with the spoken word is intrinsic to the dynamic tensions of ‘End Matter’. For Benjamin too, this tension was key to the liberating potential of allegory, which he saw as a space where: [W]ritten language and sound confront each other in tense polarity. The writer-in-residence leaves behind an audio file which records her speech and footsteps in real time; its immediacy mediated by the Adjusters bureaucratic method and presented as a forensic exhibit. Benjamin continues: The division between signifying written language and intoxicating spoken language opens up a gulf in the solid massif of verbal meaning and forces the gaze into the depth of language. This stratifying device is active both in terms of both ‘End Matter’s’ formatting and its narrative strategy, producing a text as compressed and richly layered as the geological formation of Portland stone. It evokes a vertical temporality, a coexistence of all the different eras inhabited by this slim book, ranging from the Jurassic to the contemporary. This vertical sense of time lends itself to a belief in reincarnation and the Adjusters suspicion the Rogue Adjuster has evolved into an inextinguishable life force is an irrational possibility which seeps out to encompass all the characters.

In Craig Owens’ essay ‘The Allegorical Impulse: Towards a Theory of Postmodernism’, he states: Allegory is an attitude as well as a technique, a perception as well as a procedure. It occurs whenever one text is doubled by another. One text is read through another. The paradigm for the allegorical work is the palimpsest. In ‘End Matter’ the allegorical attitude is so intensified, it conjures the supersensible as Palmer calls it. In Elizabeth Bowen’s wartime novel ‘The Heat of the Day‘ there’s a phrase which evokes the atmosphere of collective hallucination of London during the blitz, which allows for fleeting moments of intense, erotically charged, telepathic communication between the characters. She calls it: the thinning of the membrane between this and that. The thinning of the membrane between this and that, bringing lost layers of duration into stark relief, is the latent force at work in ‘End Matter’.

In other story threads produced by the writer-in-residence, the allegorical attitude is played out in a way which highlights the absurd, Kafkaesque quality of its endeavour. Most strikingly, in the case of the Rogue Adjuster where the logic of absence counterbalanced by presence is enacted in terms of the law of supply and demand. As well as stone, the island also boasts sheep which yield a particularly sweet mutton and which the Rogue exports for profit. As the Loss Adjusters summarise the situation: The Rogue realises that an overlooked consequence of quarrying is the removal of grazing land for Portland’s native sheep. In his degenerate mind, he understands that this delicacy will become rare, so he attempts to secure a supply of it for himself, to fulfill an improbable level of demand from some unspecified market. Paradoxically, the Rogue needs the land to continue to disappear in order for the sheep to become increasingly valuable. At one point the Rogue, in his greed, is compared to a pig–whose meat he himself disdains on the grounds it will happily eat human flesh. His own corpse ends up being fed to these very animals, so embodying the self-consuming cycle of supply and demand which drives market forces. This aspect of ‘End Matters’ is a cautionary tale that turns on the thinning of the membrane between human and animal, between stone and flesh. As if, beneath the skin of the landscape, there stirs an endless chain of being.

An earlier version of this review was previously published by 3:AM Magazine.

End Matter by Katrina Palmer was published by BookWorks in 2015.

Works consulted:

Walter Benjamin, The Origins of German Tragic Drama (London: Verso, 1998).

Elizabeth Bowen, The Heat of the Day (London: Jonathan Cape, 1949).

Craig Owens, 'The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism', October, 12 (1980), pp. 67–86.

Katrina Palmer, (London: BookWorks, 2015).

- Jul 25, 2025

by George Storm Fletcher

I met with the artist Hamza Ashraf, and he explained to me how he lost his residency status from his birth country – due to ‘online nudity', which also ‘outed’ him as gay. Ashraf processes his new reality of ‘statelessness’ in We Fear No God, But Ourselves – a monograph of poems, narrative scripts and photographs, which are predominantly taken with a polaroid camera.

Hamza tells me about the influence of the French writer, Annie Ernaux in his work. I have only read one of her novels, a novella of barely eighty pages, called The Young Man – which is about a break in the protagonist’s life, an intervention in the form of a love affair. Through the process of starting, and ending this brief relationship, Ernaux becomes motivated to write again, but ‘The Young Man’ is somewhat used up in the process. In his monograph, Hamza reestablishes who gets consumed by the writing process, allowing his work to sustain, rather than subsume or deplete him. The book is the first of four – it is the start of something, rather than a culmination of events. We talk about another of Ernaux’s books, The Use of Photography, which is about an affair that she has with the photographer, Marc Marie. Hamza says it is hard to know who was married, as the French call lots of things ‘affairs'. He explains how the book centres on photographs taken after the act of sex. ‘A Classic’, I say, we laugh, ‘A Classic’. Each party then writes about each photograph, but without discussing with the other person what they have written. I have not read this book, and so to some extent Ernaux’s book will always be what Hamza has told me of it. Similarly, we can take the images and personal reflections in Ashraf’s book and create a form of ‘truth’ based on what we have been shown by its author.

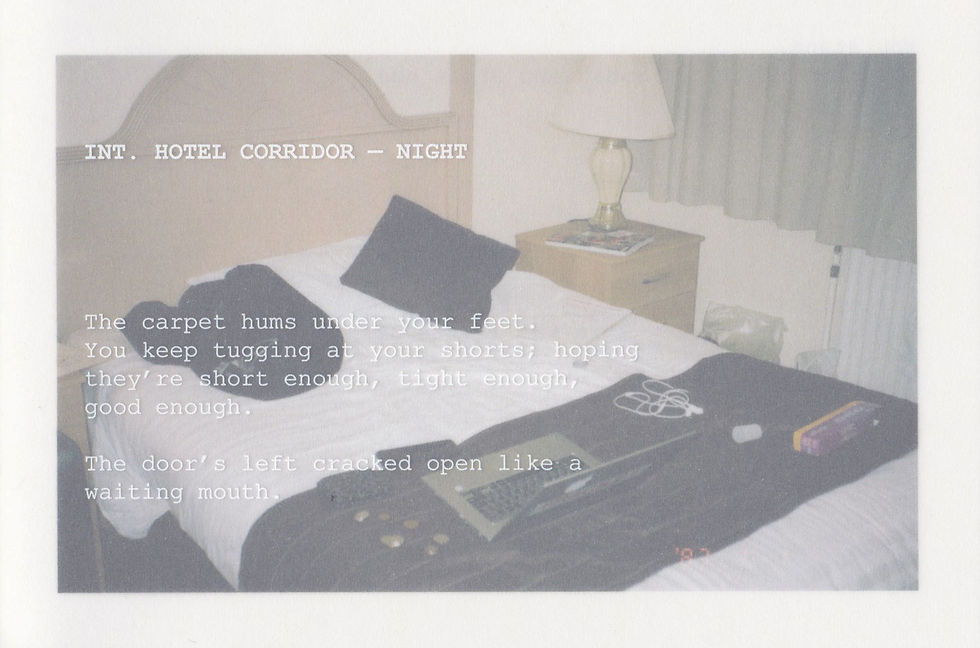

Hamza tells me that friends have referred to certain photographs in the book as ‘crime scene photos'. The images in question are in colour, but the objects strewn across the beds appear flat and lifeless. In INT HOTEL CORRIDOR – NIGHT, there is a canister of Kodak photographic film on the bed, it functions as a reminder that photography is not always documentary. Ashraf overlays prose directly on the outline of this photo. The influence of Ernaux’s photography book, of acts, and a sense of chronology is perceptible here. Ashraf’s composition tells us to directly contextualise the text to this given location, that this photograph either predates, or follows ‘an act’, perhaps of sex.

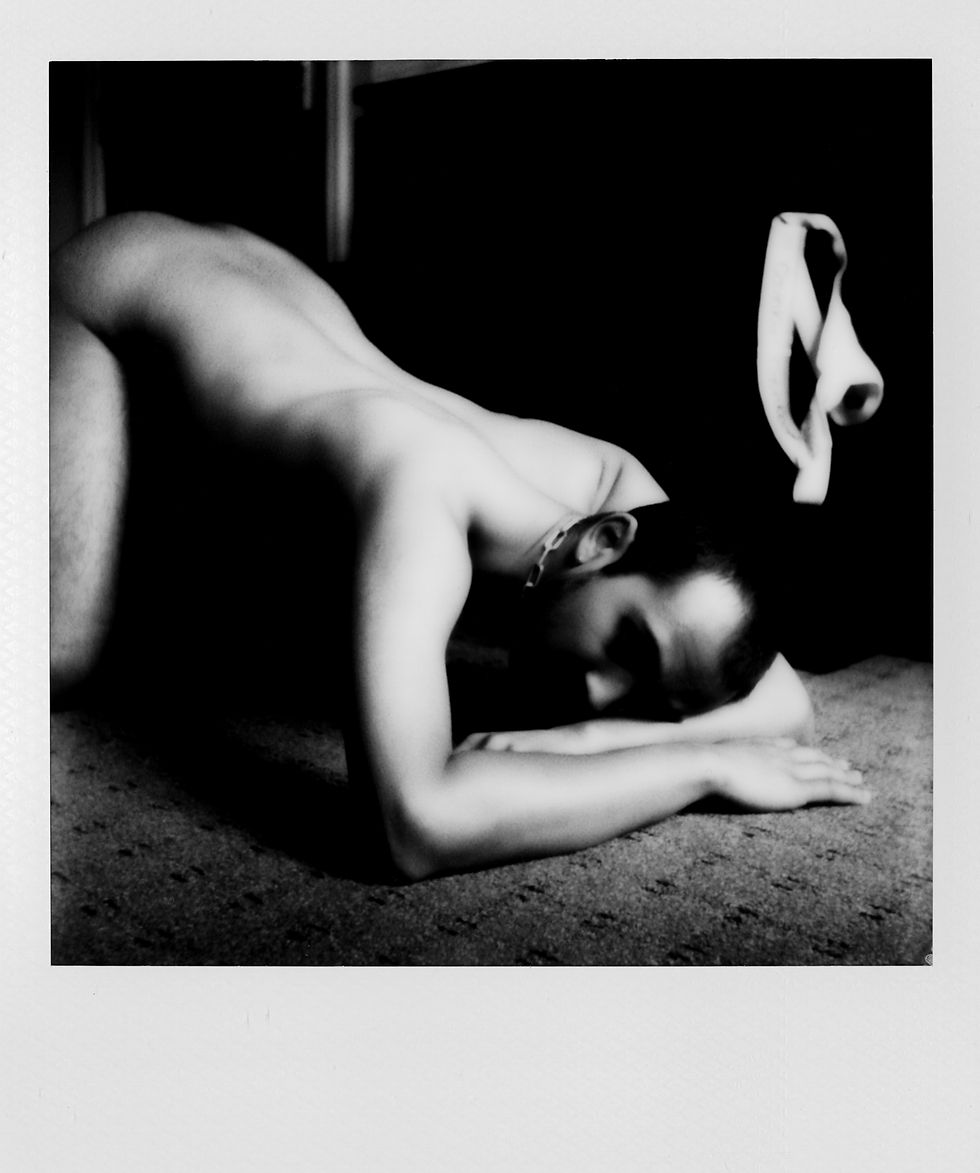

In his polaroids, Hamza spends time in the spaces, and choses a moment to set the camera on a timer. Whilst photography is a series of decisions, the use of a timer is not sharp, it blunts the gesture, softening it across time. The polaroids in the monograph are therefore an elapsed moment, in direct contrast with the precision shutter of the ‘crime scene photos'. In the hotel room act we are made aware of the presence of a voyeur, a television showing an ‘An ad for knives, cutting nothing’. Is declining the mechanical exactness of the posed portrait, and using a timer in the polaroids that follow this story, a reaction to possible violence – a refusal to cut the bodies being depicted?

Hamza and I talk about Margaret Atwood, and how she writes that we are all ‘our own voyeurs'. But there is no sense of the photographer versus the photographed in Ashraf’s work: as viewers we witness, yes, but the hand is imperceptible. Because of this, his monograph does not sexualise pain, despite repeated images of weaponry. This point is reiterated later in the script with the phrase ‘The TV keeps selling knives to no one’. If the narrative given by the metaphorical voyeur (in this case the television) is to buy knives (self-harm), then it is something that we (the protagonist) are not buying. The hand that would cut the body is not present or felt.

Hamza draws my attention to the presence of the red stitch that binds the book together. The thread is a subtle suggestion of the realities of harm in these stories. In a later image: a hand lays upon a bed, with a presence of blood on white bedsheets, creased by the body. The image is black and white, and the rhythm of the red stitch, travelling vertically on the page, in five even drops, is the only colour present to indulge in a bloody, bodily gesture. Here we are informed of possible harm, but it is an editorial decision that seeps in, and stains – like the blood on the sheet – rather than cutting us like the knives on the television.

In the proceeding script we are met with a narrative of ‘cleanliness’, the characters ‘HIM’ and ‘YOU’, converse:

HIM

You clean?

YOU

Yeah.

HIM

Good.

‘Clean’ in this context refers to the presence of STDs, particularly HIV. It is a slang commonly adopted in the queer community, but one that clearly lends itself to a metaphor surrounding shame, and particularly in this monograph, Godliness. This narrative is interrupted by the Adhan, the Islamic call to prayer, an audio-based alert that the narrative is about to change.

Whilst I am talking to Hamza, a fellow patron knocks over a glass, and we both turn to look, exemplifying the device at work. The familiarity of what the Adhan sounds like, is not needed to understand the drama of this event. We all know what it is for a phone to ring, or to jump at a sudden knock at the front door. The effect, of being taken out of the moment, and back to ‘reality', is universal. The specificity, however, is the intrusion of faith into a deed that contests HIS religion and causes the sex act to cease. Praying, and the sex act described involve bended knees, a form of deference – both are therefore forms of submission.

Ashraf’s use of nude photography, the same act that caused his ‘ban’, is understandable. Ashraf’s monograph examines choice, the decision of when to release the shutter on a camera, how and when to talk to God, when to submit oneself to kneel. Where he has previously been subjected to a loss of agency, the reclamation of these positions is a powerful gesture.

In a later section Ashraf asks, "I do not pray, Mamo, but I think about it every day. Is that not a kind of worship?" Hamza says that your Mamo is the uncle from your mother’s side. The descriptors available to explain relationships are far more accurate in Urdu. Here we meet a binary opposition – a specificity of culture, of traceable lineage; and the ‘statelessness’ that Ashraf now finds himself in.

There is an atmosphere change in the monograph. On the left page, a polaroid which depicts a man, his right eye looking towards us, the right page shows a journal entry from July 2024 that begins, "I am back to being an anxious ..... after last night honestly." The second half of the writing is redacted. An unintentional mystification occurs in the form of Ashraf’s complex handwriting. His cursive is particularly beautiful – so beautiful that it makes one question whether the point of writing is to communicate, or to express what the hand wants to say. With these illegibilities, Ashraf’s enacts what he writes in his text: "I never wanted to be whole, just the parts I could handle." As we turn the page there is a clear image, a soft green polaroid of a tree.

There is a clarity of breath in the following piece, weight of the world. Hamza tells me he allows memories in, allows himself to feel them, and then sees what ‘comes up'. But we are forced out of this space, and Ashraf writes: "The light has changed. What was once warm now cuts through the room like a blade." In the next black and white polaroid, the sitter at first appears headless, but they are not decapitated – the head is in recession as a double exposure, in a state of flux. Ashraf’s monograph communicates, through the book form, what ‘has happened’ to him – it speaks more clearly than ‘factual’ written statement could.

When we recall a memory, we are not finding an intact object, rather we recreate memories each time we remember them. Psychologist Ed Yong describes that, "Memories aren’t just written once, but every time we remember them", and in this process there is a window for ‘reconsolidation'. I am struck but how this is akin to making and editing book works. Until a work goes to print, it is subject to a series of edits, manipulations and erasures. Our readers will never see these changes, and this is exactly how our memories can work – old versions are over written, changes are lost, and revisions are made. Ashraf manipulates this process to reimagine the narrative that has been forced upon him – it is a powerful reclamation of story.

We Fear No God, But Ourselves by Hamza Ashraf

1st Edition published May 2025

Sources referenced in this review:

Margaret Atwood, The Robber Bride (New York: Doubleday, 1993), pp. 721-22.

Annie Ernaux, Marc Marie, The Use of Photography (London: Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2024).

Annie Ernaux, The Young Man (London: Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2023).

Ed Yong, on rewriting memories:

- Jun 16, 2025

by Emily Moore

The poet Gwendolyn Brooks said that she didn’t ‘have any special religion’, that her religion was ‘PEOPLE. LIV—ING’ [1]. One certainly feels this when reading any of Brooks’ work. Her characters are complete and entire, filled out from every angle, with voices that make them come alive, and contradictions that make them human. Her work has this in common with that of Gayl Jones. Indeed, it’s one of the qualities for which Jones admired Brooks. Jones wrote of Brooks’ “In the Mecca”, that it was ‘about individual, particular Afro-American human beings’ [2]. Jones’ work oozes the same faith in aliveness, takes the same joy in rendering characters in all their human vitality, in all their beauty and all their flaws.

We can see this from Jones’ first novel Corregidora, published in 1975 to much critical acclaim. The protagonist Ursa is as alive in her taciturn silences as she is in the blues she sings. Both help her to make sense of, accommodate, absorb, and heal from her lovers’ abuse and the trauma of Brazilian plantation slavery with its attendant sexual violence inherited through her foremothers. Eva, of Jones’ second novel Eva’s Man, published in 1976, tingles with this same aliveness, despite her fall into an intense psychosis, despite the fact that she commits an atrociously violent crime, and despite the hostile critical response by figures such as June Jordan who wrote that the novel ‘perpetuate[s] “crazy whore”/“castrating bitch” images that long have defamed black women in our literature’ [3]. Nevertheless, we feel Eva’s aliveness in the shadow of her past. We experience it in her madness, her psychic breakdown, the fracturing of her point of view, and the hallucinatory turn of her language. As Jones wrote of the protagonists of this novel: ‘that man and woman don't stand for men and women – they stand for themselves, really’ [4]. And we see this same human vitality in Harlan and Mosquito, the protagonists of her 1998 and 1999 novels The Healing and Mosquito. These novels, which broke Jones’ first long literary silence, mark a stylistic shift in her oeuvre. They represent the inauguration of a rambling, meandering, conversational tone – a distinctly prosodic real human voice. And it's in these novels, in this more conversational tone, that Jones starts to consider the idea of the human more explicitly; its relation to freedom, agency, racialisation, and oppression. Finally, Almeyda of Jones’ 2021 Pulitzer Prize finalist Palmares – the sweeping and lyrical first-person account of Almeyda’s escape from slavery and search for her lover Anninho and the settlement for escaped slaves Palmares – has an aliveness that is fantastical, magical, and multi-dimensional.

There are some constant elements of Jones’ innovative, incantatory style that nurture this aliveness. Her powerful orality – the repeated ‘like I said’s, the ‘I acknowledge y’all’s and the ‘Ain’t I told y’all that?’s – means there is an implicit assumption that we can really hear her characters, really see them, even talk to them, ask them questions and receive answers. Her intertextuality achieves the same thing. Her novels are littered with “easter eggs” like the allusion to the Spider Web bar in The Unicorn Woman, which is also mentioned fifty years earlier in Corregidora: ‘not the Spider where I was to work later, but the old Spider Web that was long since torn down’. Characters reappear in different novels – the newsletter of a secret society in Mosquito contains references to The Birdcatcher’s Catherine, The Healing’s Joan, and Amanda Wordlaw, a phantom writer who features in several of the novels. The “Jonesiverse” is like a kind of truth claim. The characters and the places they go to have real lives that extend beyond the confines of their novels and seep into others. And Jones talks about her characters like they are real, agentive beings. She says, ‘I really did think Ursa would stay with Tadpole. I really didn't expect him to do what he did’ [5]. Her characters have their own lives, their own wills, and make their own decisions independently of their author.

We might take Jones’ commitment to her characters’ aliveness for a kind of humanism. Famously reclusive, publishing in flurries of activity between long silences, and having given no interviews for over twenty years, Jones hasn’t explicitly engaged with the debates swirling within the field of Black Studies between the Afropessimists and the Humanists: debates as to whether the anti-Black violence which has excluded Black people from the category of the Human – as theorised in the Enlightenment and upon which modernity relies – has effected a unique kind of social death; or whether it might be possible to replace this exclusionary idea of the Human with a multifarious, inclusive, and fluid planetary humanism.

So, we don’t explicitly know what she thinks about how to deal with the legacy of slavery’s dehumanisation. But she does seem to share Brooks’ commitment to using the tools at her disposal, her literature, to represent Black people in the fullest, most vibrantly ambivalent reality possible. Hers is a humanism then, of storytelling. Her characters come alive in books. Maybe we can contextualise this idea within the history of Black people being banned from literacy in the US during the period of the Atlantic slave trade. And we might also relate it to the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s which celebrated oral tradition in literature – real Black human voices. But Jones’ humanism is about more than just finding a voice in the textual, and its more than empowering oral traditions by embedding them in literature. Her storytelling performs a kind of healing work – a revivification. She redraws the concept of the human by creating Black characters who are irrepressibly and incontrovertibly alive. She undoes social death by declaring social life. The concept of the social is important because Jones’ humanism is of the world. It’s not the liberal humanism of 1950s New Criticism that saw texts as independent of social, political, and historical contexts and assumed the fixed and stable nature of the human subject. Her humanism, rather, entails many implications and contexts. It’s important to talk about the social here, because Jones’ stories aren’t just about humans, but the relationships between them: between characters; but also, in Jones’ words, ‘between the teller and the hearer; and ‘between the storyteller and the story’. These are the virtues Jones recognises in “storytelling” – it’s inherent ‘human connections’ [6].

Jones’ most recent publication, her seventh novel, The Unicorn Woman, is a contemplation and confirmation of her particular iteration of humanism. It tells the story of Buddy Johnson (Mosquito’s uncle), a tractor repairman and WWII veteran. Having returned to Kentucky from France, ‘sometime after the Second World War’, he sees the Unicorn Woman (a woman with the horn of a unicorn in the middle of her forehead) at a carnival and is enthralled [7]. The search for her – or ‘hunt’ as the novel puts it – consumes him. He consults doctors and healing women with questions about her and all other romantic partners fall short of her image in his mind. Although populated by women griots, healers, jokesters – the kinds of alive woman that we’re used to getting to know in Jones’ novels – Jones’ humanism is expressed differently here. The Unicorn Woman – as a motif, as a symbol, as a woman, and as a character in a story – becomes a way of thematising and contextualising the humanism evident across Jones’ oeuvre. She is a way of invoking and inspecting the fraught relationship between Blackness and the notion of the Human: the way in which the modern definition of the Human has depended on the degradation, dehumanisation, and oppression of a racialised Black other.

There is the implicit suggestion throughout that we might take the Unicorn Woman’s horn as an analogy for Blackness. Though this is certainly not a straightforward analogy. It is complicated, for example, by the fact that the Unicorn Woman is herself Black. One spectator says, ‘“They don’t have colored unicorns. All the unicorns I’ve ever seen have been white”’. It is complicated also by the gender dynamics at work in Buddy’s pursuit of her. And finally, that the Unicorn with its horn is a decidedly European symbol disrupts this easy comparison. Tentatively overlooking these confounding elements, however, let’s pursue this thread a little further.

If the Unicorn Woman’s horn functions as an analogy for Blackness, it is not Blackness as an essentialised, unchanging, innate quality, but Blackness as a racialised construct that has been used to enact oppression and dehumanisation. It’s the thing for which the Unicorn Woman is fetishised – ‘“maybe it’s easier to ask people about the horn than the woman”’. It’s the thing people use to declare her non-human – ‘“He thinks my horn means I’m a devil”’. It’s the thing that prompts consideration of what makes anyone human – ‘“That would be something wouldn’t it? If every human being had a horn?”/“Yes, it would sure be something. But if we all had horns, it would just be a natural thing.”’ It represents something for the people that come to see her – ‘“it’s the horn, not me. It represents something for ‘em”’. But there is also the acknowledgement that it’s something that might empower her – ‘“Because that horn is her signature. I mean it has significance. I don’t know what that horn might mean and neither do you. And I don’t know what might be in that horn. Maybe that horn is as special to her as her soul is”’. And it prompts consideration of what everyone’s own “horn” is – ‘“A horn can be anything [...] I ain’t gonna tell you what my horn is though”’. Thus, the horn might provide a way of relating to one another. The Blackness the horn is compared to then, has many implications and meanings.

Alongside this analogy is the novel’s insistence on the humanness of the Unicorn Woman. We often overhear spectators of the carnival show asserting this, saying things like, ‘“She’s a human woman; she ain’t no goat or a lamb”’. But there’s more to the novel’s elaboration of Jones’ humanism than this insistence. It’s not simply that Jones equates the Unicorn Woman’s horn with Blackness and then insists that she is human. Rather, the horn is a way of contextualising the uses of this Blackness.

The symbol of the Unicorn Woman is a way of deftly reminding us of the painful aspects of the history of Black performance. Either explicitly or implicitly, Jones alludes to various ways in which Blackness has been (and, as she reminds us, continues to be) treated as a spectacle. She acknowledges the bleak and disgraceful history of Black individuals being spectacles at exhibitions, sideshows, and carnivals. One character talks about avoiding carnivals because of an exhibit called ‘The African Dodger’, which involved ‘“making fun and games out of hitting colored people and throwing balls at them"’. There’s an oblique reference to Sarah Baartman (a woman exhibited in the early nineteenth century as “The Hottentot Venus”) as Buddy talks about ‘Venus of Willendorf hips’ in a story he writes. He also dreams that he himself has become a sideshow exhibit: ‘“What makes him a wonder? He looks like an ordinary colored man to me”’. Jones invokes the coerced and misinterpreted incidents of song or dance at terror-laden performance sites such as the auction block, the coffle, or in front of enslavers by reminding us that ‘“the struggle of the old slave continues into this day and time”’. Finally, Jones makes reference to the unruly and uncontainable legacy of minstrelsy and Blackface performance and the exploitative, fetishistic, and exoticising elements of the modern Black entertainment industry. Spectators’ comments make this connection for the reader: ‘“She kinda remind me of Billie Holiday, Lady Day”' and ‘“She reminds me of a songstress”’. All of these references are present in the figure of the Unicorn Woman. She becomes a symbol for this painful performance history.

But there are dangers in this analogy. Does this symbolism strip the Unicorn Woman of her humanity? Is her voicelessness a problem? Do we as readers somehow become complicit in her dehumanisation?

Firstly, although Jones reminds us throughout of the fact that the Unicorn Woman is ‘“a human woman”’, she ends up bearing huge symbolic weight. As a symbol of Black performance history, an exemplar of the process by which modernity’s Man is defined opposite and against the racialised other, the Unicorn Woman becomes not quite human. She represents historical and fetishised Blackness. Of all Jones’s literary creations then, she remains most enigmatic, most bereft of the vital humanity that usually characterises them.

And secondly, what of the fact that, despite the reminders of her humanness, we don’t ever hear her actual voice? It’s often ventriloquised through Buddy’s dreams and imagination, but the Unicorn Woman herself remains silent. This is striking in light of Jones’ deep association between voice and personhood; between ‘the liberated voice’ and the ‘“whole consummate being”’ [8]. Is this an unfortunate coincidence? This is Jones’ first novel written from a male perspective. It’s an attempt she has long been planning. (In 1988, she wrote ‘I should probably try that with a novel—just to try it—to see how the man would order his world’ [9].) By finally realising her desire to explore the male perspective in this novel, has she set up a plot that inadvertently accomplishes the very thing she has spent her career railing against?

It’s hard for us to believe strongly in the humanness of the Unicorn Woman, to undo the process of fetishisation when she remains so resolutely abstract and voiceless. So, she does end up becoming the spectacle, the gazed-upon oddity, that we are told she is not. Are we lured into believing too rigidly in the analogy between her horn and Blackness? Do we thus become complicit in her fetishisation? In rendering her non-human? Is Jones, as she so often does, making us uncomfortable on purpose? Why does Jones’s Unicorn Woman partake in the silencing of the protagonist’s humanism that she elsewhere fights against?

Jones must be doing this on purpose. The novel must be a deliberate demonstration of dehumanisation. It enacts the dehumanisation process, enacts the impossibility of love under conditions of inequality, enacts the impossibility of escape from the traumata of Black history in the US. It enacts exactly the dangerous error noted by the poet Audre Lorde in her poem ‘The Black Unicorn’ where ‘The black unicorn was mistaken/for a shadow/or symbol’ [10]. The plot becomes a metaphor. The novel, or rather, storytelling becomes a tool in making clear to us what is at stake in the idea of literary aliveness.

And it’s not only the plot that serves as a metaphor. Buddy’s storytelling voice, his interest in words, sounds, meaning, and naming achieves something similar. He gives us the sense that language is not what it at first seems. There are slippages, doublings, and contradictions. As a child he hears his name, Bud, in the expression ‘a little bird told me’; he refers to ‘a din of iniquity’; he confuses ‘farmer soldiers’ and ‘former soldiers’, ‘colored flours’ and ‘colored flyers’. The mishearings go on and on, multiplying meanings each time, highlighting the audibility of the words and the contingency of meaning upon sound. All of this relates back to the novel’s meditation on spectacle and racialisation. These mishearings parallel the effect of the Unicorn Woman’s horn. The horn means many things at once. It’s made to stand for one thing, but many possibilities lurk beneath, like the various meanings veiled behind the words on the page, hidden in sound, in unexpected aural similarities. Language then, like plot, becomes a metaphor, a metaphor for the novel’s blurring of the line between reality and unreality, between the reality of a human woman and the unreality of a mythical unicorn, or, analogously, between a Black human woman and a Black woman figured as non-human. In this way, writing, words, and storytelling become tools to resist dehumanisation and degradation. Once again, they are a means of declaring Black humanity, not just by representing Black voices, but by being wrung for all their power, all their aesthetic, representational, symbolic magic. In Jones’ own words, ‘The language is no longer flat and one dimensional. You have the sense that [storytellers are] trying to make the language do things. And it's not just to be playing with words, either; they have a stake in it’ [11].

The Unicorn Woman by Gayl Jones

London: Virago, 2024

Notes

[1] Conversations with Gwendolyn Brooks, (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2003) p. 102.

[2] A Life Distilled: Gwendolyn Brooks, Her Poetry and Fiction, (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987), p. 201.

[3] Jordan, June, “All About Eva: Eva’s Man”, New York Times Book Review (16 May 1976), pp. 36.

[4] Harper, Michael S., ‘Gayl Jones: An Interview’, The Massachusetts Review, Vol. 18, No 4 (Winter 1977), pp. 701.

[5] Harper, ‘Gayl Jones: An Interview’, p. 696.

[6] Harper, ‘Gayl Jones: An Interview’, p. 695.

[7] All citations of the text from Jones, The Unicorn Woman, (London: Virago, 2024).

[8] Jones, Liberating Voices (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991) p. 178.

[9] Jones, ‘About My Work’ in Porter, H. A. (ed.), Dreaming Out Loud: African American Novelists at Work (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1988), p. 111.

[10] Lorde, Audre, ‘The Black Unicorn’, (London: Penguin Classics, 2019) p. 4.

[11] Harper, ‘Gayl Jones: An Interview’, p. 706.