Hamza Ashraf: We Fear No God, But Ourselves

- Jul 25, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Aug 26, 2025

by George Storm Fletcher

I met with the artist Hamza Ashraf, and he explained to me how he lost his residency status from his birth country – due to ‘online nudity', which also ‘outed’ him as gay. Ashraf processes his new reality of ‘statelessness’ in We Fear No God, But Ourselves – a monograph of poems, narrative scripts and photographs, which are predominantly taken with a polaroid camera.

Hamza tells me about the influence of the French writer, Annie Ernaux in his work. I have only read one of her novels, a novella of barely eighty pages, called The Young Man – which is about a break in the protagonist’s life, an intervention in the form of a love affair. Through the process of starting, and ending this brief relationship, Ernaux becomes motivated to write again, but ‘The Young Man’ is somewhat used up in the process. In his monograph, Hamza reestablishes who gets consumed by the writing process, allowing his work to sustain, rather than subsume or deplete him. The book is the first of four – it is the start of something, rather than a culmination of events. We talk about another of Ernaux’s books, The Use of Photography, which is about an affair that she has with the photographer, Marc Marie. Hamza says it is hard to know who was married, as the French call lots of things ‘affairs'. He explains how the book centres on photographs taken after the act of sex. ‘A Classic’, I say, we laugh, ‘A Classic’. Each party then writes about each photograph, but without discussing with the other person what they have written. I have not read this book, and so to some extent Ernaux’s book will always be what Hamza has told me of it. Similarly, we can take the images and personal reflections in Ashraf’s book and create a form of ‘truth’ based on what we have been shown by its author.

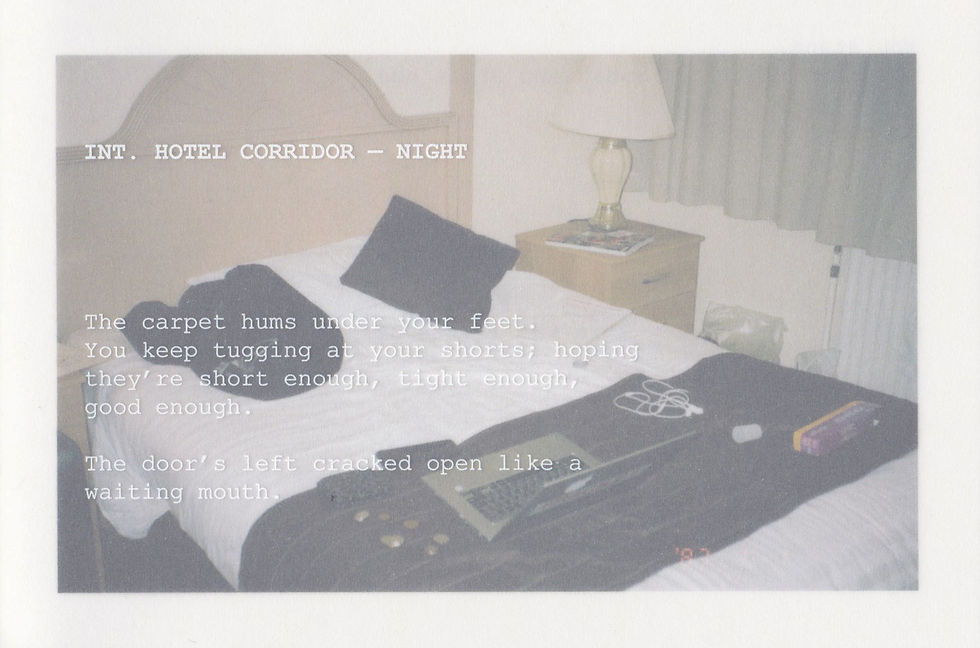

Hamza tells me that friends have referred to certain photographs in the book as ‘crime scene photos'. The images in question are in colour, but the objects strewn across the beds appear flat and lifeless. In INT HOTEL CORRIDOR – NIGHT, there is a canister of Kodak photographic film on the bed, it functions as a reminder that photography is not always documentary. Ashraf overlays prose directly on the outline of this photo. The influence of Ernaux’s photography book, of acts, and a sense of chronology is perceptible here. Ashraf’s composition tells us to directly contextualise the text to this given location, that this photograph either predates, or follows ‘an act’, perhaps of sex.

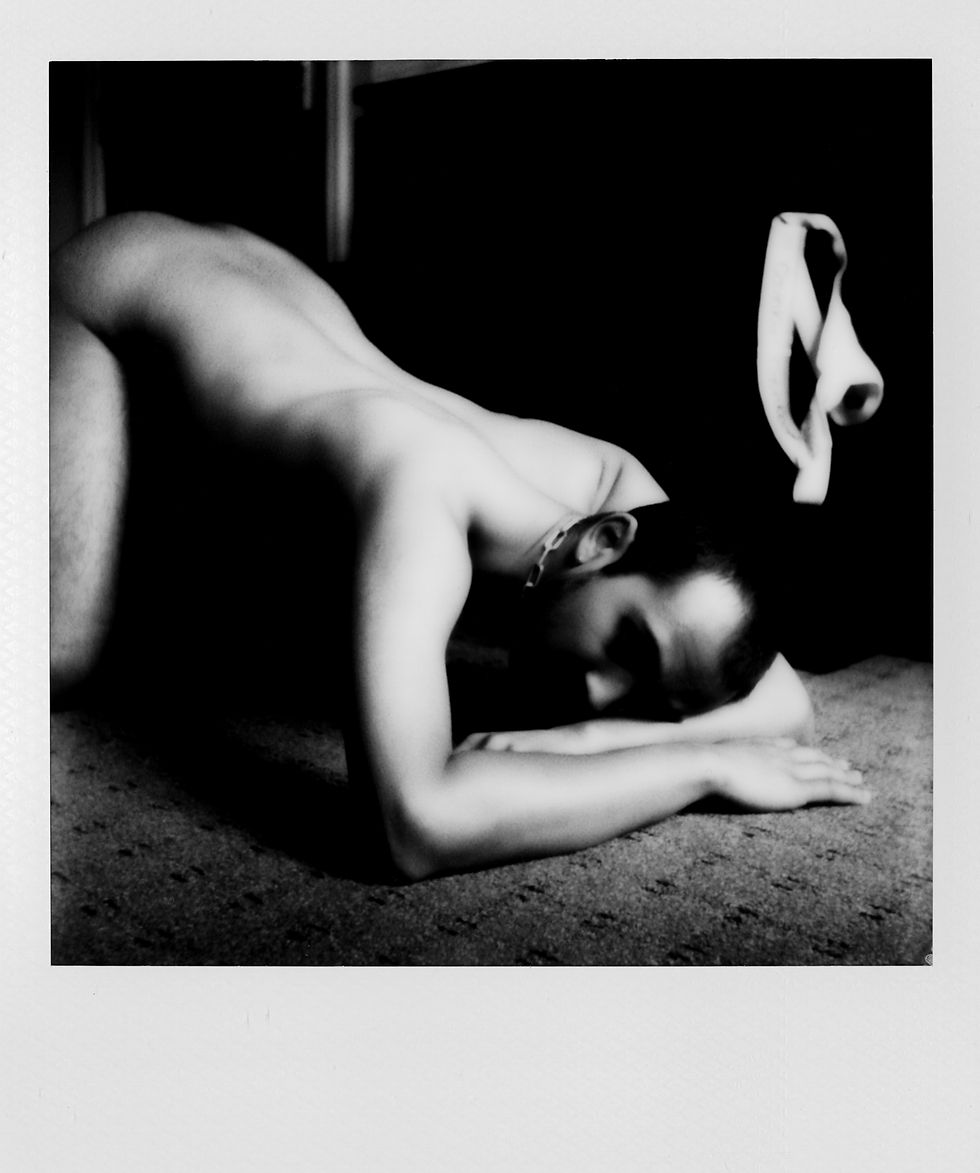

In his polaroids, Hamza spends time in the spaces, and choses a moment to set the camera on a timer. Whilst photography is a series of decisions, the use of a timer is not sharp, it blunts the gesture, softening it across time. The polaroids in the monograph are therefore an elapsed moment, in direct contrast with the precision shutter of the ‘crime scene photos'. In the hotel room act we are made aware of the presence of a voyeur, a television showing an ‘An ad for knives, cutting nothing’. Is declining the mechanical exactness of the posed portrait, and using a timer in the polaroids that follow this story, a reaction to possible violence – a refusal to cut the bodies being depicted?

Hamza and I talk about Margaret Atwood, and how she writes that we are all ‘our own voyeurs'. But there is no sense of the photographer versus the photographed in Ashraf’s work: as viewers we witness, yes, but the hand is imperceptible. Because of this, his monograph does not sexualise pain, despite repeated images of weaponry. This point is reiterated later in the script with the phrase ‘The TV keeps selling knives to no one’. If the narrative given by the metaphorical voyeur (in this case the television) is to buy knives (self-harm), then it is something that we (the protagonist) are not buying. The hand that would cut the body is not present or felt.

Hamza draws my attention to the presence of the red stitch that binds the book together. The thread is a subtle suggestion of the realities of harm in these stories. In a later image: a hand lays upon a bed, with a presence of blood on white bedsheets, creased by the body. The image is black and white, and the rhythm of the red stitch, travelling vertically on the page, in five even drops, is the only colour present to indulge in a bloody, bodily gesture. Here we are informed of possible harm, but it is an editorial decision that seeps in, and stains – like the blood on the sheet – rather than cutting us like the knives on the television.

In the proceeding script we are met with a narrative of ‘cleanliness’, the characters ‘HIM’ and ‘YOU’, converse:

HIM

You clean?

YOU

Yeah.

HIM

Good.

‘Clean’ in this context refers to the presence of STDs, particularly HIV. It is a slang commonly adopted in the queer community, but one that clearly lends itself to a metaphor surrounding shame, and particularly in this monograph, Godliness. This narrative is interrupted by the Adhan, the Islamic call to prayer, an audio-based alert that the narrative is about to change.

Whilst I am talking to Hamza, a fellow patron knocks over a glass, and we both turn to look, exemplifying the device at work. The familiarity of what the Adhan sounds like, is not needed to understand the drama of this event. We all know what it is for a phone to ring, or to jump at a sudden knock at the front door. The effect, of being taken out of the moment, and back to ‘reality', is universal. The specificity, however, is the intrusion of faith into a deed that contests HIS religion and causes the sex act to cease. Praying, and the sex act described involve bended knees, a form of deference – both are therefore forms of submission.

Ashraf’s use of nude photography, the same act that caused his ‘ban’, is understandable. Ashraf’s monograph examines choice, the decision of when to release the shutter on a camera, how and when to talk to God, when to submit oneself to kneel. Where he has previously been subjected to a loss of agency, the reclamation of these positions is a powerful gesture.

In a later section Ashraf asks, "I do not pray, Mamo, but I think about it every day. Is that not a kind of worship?" Hamza says that your Mamo is the uncle from your mother’s side. The descriptors available to explain relationships are far more accurate in Urdu. Here we meet a binary opposition – a specificity of culture, of traceable lineage; and the ‘statelessness’ that Ashraf now finds himself in.

There is an atmosphere change in the monograph. On the left page, a polaroid which depicts a man, his right eye looking towards us, the right page shows a journal entry from July 2024 that begins, "I am back to being an anxious ..... after last night honestly." The second half of the writing is redacted. An unintentional mystification occurs in the form of Ashraf’s complex handwriting. His cursive is particularly beautiful – so beautiful that it makes one question whether the point of writing is to communicate, or to express what the hand wants to say. With these illegibilities, Ashraf’s enacts what he writes in his text: "I never wanted to be whole, just the parts I could handle." As we turn the page there is a clear image, a soft green polaroid of a tree.

There is a clarity of breath in the following piece, weight of the world. Hamza tells me he allows memories in, allows himself to feel them, and then sees what ‘comes up'. But we are forced out of this space, and Ashraf writes: "The light has changed. What was once warm now cuts through the room like a blade." In the next black and white polaroid, the sitter at first appears headless, but they are not decapitated – the head is in recession as a double exposure, in a state of flux. Ashraf’s monograph communicates, through the book form, what ‘has happened’ to him – it speaks more clearly than ‘factual’ written statement could.

When we recall a memory, we are not finding an intact object, rather we recreate memories each time we remember them. Psychologist Ed Yong describes that, "Memories aren’t just written once, but every time we remember them", and in this process there is a window for ‘reconsolidation'. I am struck but how this is akin to making and editing book works. Until a work goes to print, it is subject to a series of edits, manipulations and erasures. Our readers will never see these changes, and this is exactly how our memories can work – old versions are over written, changes are lost, and revisions are made. Ashraf manipulates this process to reimagine the narrative that has been forced upon him – it is a powerful reclamation of story.

We Fear No God, But Ourselves by Hamza Ashraf

1st Edition published May 2025

Sources referenced in this review:

Margaret Atwood, The Robber Bride (New York: Doubleday, 1993), pp. 721-22.

Annie Ernaux, Marc Marie, The Use of Photography (London: Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2024).

Annie Ernaux, The Young Man (London: Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2023).

Ed Yong, on rewriting memories:

Comments